Making the Case for Manufacturing – Made in the USA Transcript

The majority of Americans want to “bring manufacturing back” to the U.S. The problem? Many of these same people do not want their children to work in manufacturing because of outdated beliefs about what a machine shop looks like.

Pete: The important factor we are going to talk about in this episode is subtle, it’s invisible, but it’s powerful. I am talking about the perception of manufacturing: the perception of what manufacturing is, what it looks like, what it consists of.

What we believe can change that truth. In U.S. manufacturing, we are challenged, in part, because many Americans believe that manufacturing, or specifically, employment in manufacturing, is something different and perhaps more limited or challenged than it actually is.

Pete: Right, so let’s talk about some of the misperceptions. Here is one: people think manufacturing and they think “factory.” They imagine boring, repetitive work, maybe like an assembly line. They also imagine work described by the 3 “D’s”: dark, dirty, dangerous. The truth: much of manufacturing now happens in lightly staffed operations that don’t look much like factories. The mundane, repetitive work has largely been automated. And some of the most modern manufacturing facilities using the latest technologies are as clean, as quiet, as comfortable and safe as any office you might work in.

Brent: I can think of another misperception. Episode 2 of this podcast focused on automation. And we talked about this belief that manufacturing jobs are disappearing because automation is taking their place. But the truth is pretty strikingly different!

Sometimes automation does lead to job losses, but the effect is localized and temporary. Over time, the effect of automation has been to make skilled manufacturing jobs more valuable and more in demand. Someone has to program, maintain and oversee all the automation.

Pete: These misperceptions have a real effect. They have shaped the reality we now find ourselves in. And when it comes to manufacturing, it’s meant that when young people are imagining careers for themselves, they don’t consider manufacturing or work in CNC machining. They discount it or they don’t think it can offer them a good future. This effect on the American workforce limits how far and how fast U.S. manufacturing can expand.

Now, to some extent, this is a good thing. It is a good thing for people who have those manufacturing skills because they are in demand. Their work is valuable enough that it might never be really easy for manufacturers to find the staffing they need. We want U.S. manufacturers competing for talent. But the talent pool today for manufacturing engineers and skilled manufacturing tradespeople in the U.S. is low enough that healthy competition is often undone by the lack of any viable prospects at all.

You and I report on machine tools, the machine tool industry. This is the foundation of U.S. manufacturing, the machines that make machines. And the companies supplying this equipment often hear from their customers: we could buy more equipment, we have the potential demand to fill more machines, but can you find us another programmer or another machinist to let us run them?

Brent: So, the topic of perception versus reality in U.S. manufacturing is super important! How do we make the case for manufacturing? How do we showcase the value of this work so that capable people direct their professional careers toward it?

Because we have to get it right. If we are truly going to experience the reshoring of manufacturing back to the United States, if we are going to reevaluate where manufacturing happens and decide that we want more manufacturing to return to the United States — that can only be successful if there are more people ready and able to commit to skilled manufacturing jobs.

So let’s begin by recognizing: this is a distinctly American problem. It might be the case that people in other countries have an outdated sense of the truth of manufacturing, just as we all have outdated notions about a lot of things. But this outdated view of manufacturing seems particularly acute in the United States. In much of Europe, for example, manufacturing is recognized as a vibrant, high-tech professions, and there are wide open pathways for students to pursue it.

A leading voice on this topic is someone we’ve heard from before on this program. Here’s Scott Smith, who is the group leader for machining and machine tool research with Oak Ridge National Laboratories.

Scott Smith: You know, we spent a generation telling people that manufacturing jobs were not good jobs, and they were going away and you needed to do something else. And now, we’re surprised that there’s a silver tsunami, that there’s not people who have the right skills and all the ones who do are retiring. But we spent a generation saying that that manufacturing was dirty and dangerous and, and not where you’re going to make a good living, and nothing could be further from the truth.

Scott Smith, Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Photo Credit: Oak Ridge National Laboratory

So in Germany, they have been quite successful, for example, with the Fraunhofer institutes you’re probably aware of these right? They work in sort of a mid TRL range. So the basic research kind of stuff is in technology readiness level 1, 2, 3. And the Fraunhofer is work that’s more in the 4 through 7 kind of range. And they work with industry partners, and the decision makers in the companies are engineers, and many of them have flowed through Fraunhofer into industry

There is a pathway for people who are engineers at university studying manufacturing, who then do further work at a Fraunhofer Institute, but they don’t intend to spend their life as a researcher in the Institute. They flow through the institute and out into companies. So that’s a very efficient form of technology transfer. Because they have to have a big system of people doing that. And so I think we definitely need more investment at the high school and community college level in manufacturing related technologies, because those are good jobs. But we also need it at the university level, we need to have manufacturing You know that there used to be powerhouse manufacturing universities across the United States. And in many of those places, it’s just almost gone. So we have to get that back. And then we need a system that looks like Fraunhofer, where there is industrially relevant, mid-TRL level research going on. And people flow from the universities through those research facilities and out into companies.

Pete: He talks about TRL, or “technology readiness level.” This is a nine-level scale used to describe how close a research topic is to becoming a technology that is used or available out in the commercial world. His point is that a lot of the research in the U.S. that is relevant to manufacturing occurs at low TRL — still very abstract. In Germany, there is a system for supporting industry with research at higher TRL. This has two effects: one, manufacturers are helped by this; they get innovations they can sometimes use. And two, the work creates a way of meeting and beginning to work with engineering talent going through school.

But let’s contrast that with his first statement: what we’ve been telling ourselves, or telling children, for a generation or so about manufacturing, what is is and how it works. There is no one single culprit here, but when this one manufacturing business owner looks for a cause, one that she finds is a 1970s TV sitcom.

Heidi Hostetter, Vice President of Fauston Tool: As baby boomers, which I am, right… and Gen Xers, we kind of have this idea about the environment that our child’s exposed to, which couldn’t be more wrong. So it’s kind of like, did you ever see Laverne & Shirley? Like, do-rags and dark, dingy, greasy? And the pay is shitty? No real challenge and you’re stuck in that same role forever. Right? And not only the environment, but will my child have a chance to excel? And the answer is, Oh, my God. yes! Absolutely. Like, again, some of these folks — welders, high precision machinists — they can easily make six figures, for sure. Now, will they have to invest five to seven years in the trade? Sure, but you’d also have to in any career you choose. Quite frankly, right now when student debt is outrageous federally, right, it’s an issue that has to be addressed.

Brent: I think the takeaway here is that this is all Laverne & Shirley’s fault! Ok, maybe not, but that was a TV show from decades in the past that portrayed a time, the 1950s, that was even farther in the past. And that’s relevant to this conversation. Americans today, including parents who influence their kids’ career choices, carry outdated views of manufacturing. And yes, that even includes you Gen X-ers and Millennials.

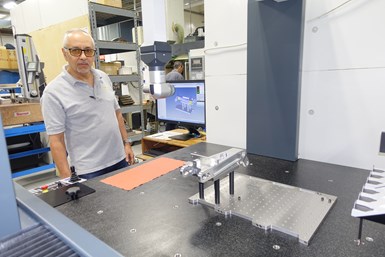

But the thing is, these are not entirely unfounded views. Manufacturing work did used to look very different than it does today. Here’s our friend DiMarino, owner of Linda Tool, an independent precision machining business in Brooklyn, New York.

Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool. Photo Credit: Linda Tool

Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool: When you were a kid, you got a job in a in a shop because you know, you could you could just go in and didn’t mean anything. So if you got caught if you got covered with oil smoke, I was welding sniffing. Okay, today. Parents that did that. they did that and it was tough. You know, it was no air conditioning in the shop. You know, you’re hot and hot in the in the summer, cold in the winter. So now they went out and got jobs in finance or doing something And their kids are growing up. They say, you know what, that’s what they remember. Because they’re not exposed anymore so they say I don’t want my kid doing that I’m chasing them by work like a dog carrying heavy stuff and banging my fingers up and breathing bad stuff in I don’t I don’t want my kid doing that thing. Now you’ve been in my shop. You can’t find a chip in my shop. You know, it’s difficult you need to you need a blood down to find one. There’s no smoke, there’s no dirt, there’s no oil, you know, people that possibly work in the industry as not an apprentice but as a starter simply just the general labor that they remember shops like that. So they want their kids to go elsewhere.

Brent: This is Doug Woods, president of AMT — the Association for Manufacturing Technology.

Doug Woods: When I used to work in my grandfather’s tool and die company as an apprentice, I used to always get the course crappy jobs… as an apprentice you get whatever they toss at you sometimes. When we would install big systems at the General Motors plant, you know, you would have to go and be part of the runoff as they’re testing and so I remember putting a windshield wiper assembly line into a Delco plant. And, you know, they sent apprentices over to help do part of the process. And at that point, it wasn’t heavily automated, I would say it was only partially automated. And so I can remember going in and sitting down on a typical steel stool in front of an assembly line, where you had to put these plastic gears with a little bit of lubricant into the wiper motor assembly, all day long, eight hours a day.

Pete: That was manufacturing. We talk about the perception of manufacturing, the misperception, but we need to be real: it comes form an authentic place. People today have memories of manufacturing as something difficult, or tedious, that they wouldn’t want to build their professional career on. In high school, I worked in a repetitive manufacturing assembly job. Not something I ever found in interest in. But a whole lot of manufacturing now, a much larger share than in the past, is creative, innovative, technically challenging work.

Rob Ireton: I think I would like to be able to wave a magic wand and kind of take some of the negative connotation associated with manufacturing away. I think a lot of people still think of manufacturing as a less clean environment to work in, a low paying job where, you know, you’re toiling all day long at the same task over and over again. One of the benefits of Plethora is that because we don’t look at the same parts day in and day out, every day brings a different challenge. And you have to have that mindset that you are not only machinists, but you’re also a little bit of a part detective and also a big problem solver, because not everything that comes off of the shop floor is perfect. So that’s really where the human element and the training and the desire really comes from. And I would like most of the United States to understand that, that you can do just as well working with CNC machine as you could working at, say, a bank or something like that. And the fact that I would venture to say that in a certain point, you’d probably find it a little more rewarding to, because at the end of the day, you can say, Hey, look what I’ve done! I have created this out of a block of alloy. And it’s kind of an interesting thing.

Pete: Jobs like the ones at Plethora are out there, creative and stimulating jobs in manufacturing, and they go unfilled. The result of our self-talk about manufacturing has been a lack of students entering manufacturing, and that has resulted in a narrowing of the channels that are even available for preparing potential manufacturing professional for these kinds of careers. Contributing to this is an over-emphasis on four-year education, when in many cases, skilled trades are in greater demand. Here again is Heidi Hostetter.

Heidi Hostetter: I think many many years ago when we did away with the vocational and the tech schools, you know, manufacturers started to feel the hit. Machinists, welders, trades, trade positions… and we started to see this real push toward this, you know, white collar, four year degrees, things like this. So eventually, that pool dried up for trade, tradesmen, machinists in my case. And so really it became about educating parents again on the trades, not necessarily the kids. The kids are really typically aware of what they want. They may be steered differently. Like I’m looking for aerospace machinists. So you’ve got to be pretty stellar at math, right? So this is a basic example. They might get immediately pushed into engineering or like a mechanical engineering role, when really they know they want to work with their hands. And I could say that because we have a lot of mechanical engineers that come out of say, Colorado School of Mines, who gave mechanical engineering a shot for a year or two and went, this isn’t at all what I wanted. And they end up coming over to us as you know, aerospace or high-end precision machinists. So we’ve really had to start to educate our parents in this community at least, to say, hey, it’s a good career. They get benefits, and know what, they’re really awesome about it and stick with it and progress through the chain. They’ll make six figures. And guess what? They don’t have near the amount of debt.

Brent: Tuition debt, salary—she’s talking about the benefit of these careers to the people who pursue them. That is significant.

But we started this episode, and this series really, with a larger goal: to showcase the value of manufacturing to the country as a whole, and to explain how our perception of manufacturing is standing in the way of that.

If a negative public perception of manufacturing leads to reduced investment in it, including people’s investment of their work and their talents, then our ability to expand, advance and flourish in the area of manufacturing is going to suffer. An along with it, our ability to innovate, invent and create things.

Scott Smith: Manufacturing and innovation are intimately tied together. And you really can’t have the innovation unless you’re actually making this stuff.

Doug Woods: Apple was a really, you know, an unbelievable company when it came to manufacturing, they did a lot of their own manufacturing — everything from developing their own circuit board technology, disk technology. And then what happened over the years is they kind of said, you know, what, I don’t know that we can scale and be efficient. So let’s get out of being in the manufacturing business. Let’s outsource that. And so obviously names like Foxconn jump to, you know, everyone’s attention when it comes to that. What Apple found was, over the years, their ability to efficiently make really cool products started to go down and down and down, not because they didn’t have good design engineers, but they realize good design engineers have to be coupled at the hip with good manufacturing design engineers. And if you didn’t really understand how products were made, if you didn’t really understand how they were automated, the really the coolest design in the world can’t be made in such a way that those two things linked to make perfect harmony. And you found that Apple went back and started hiring, you know, design manufacturing engineers again and started getting into a little bit of the manufacturing again, because those core elements have to go together.

Pete: Doug sees a lesson from Apple, but Scott Smith mentions the item we keep on returning to in this series, a key product for U.S. manufacturing or any manufacturing: machine tools. Our listeners who have long connections to manufacturing are apt to recognize some of the names he mentions of companies that played important roles in the history of the U.S. machine tool industry.

Scott Smith: It was particularly true in the machine tool world. If you look back at you know, Ingersoll: Ingersoll was thrived through the personal intervention of Edson Gaylord I think the question that we ought to be asking is why didn’t other new Ingersolls arise? Right? There’s a need for those products. So where is the new Bridgeport? Where is the new Ingersoll? Where is the new Giddings & Lewis? Where’s the new Timkin? How do we lose these things? If you want to build a machine, when you lose the industries, then you also lose the support industries.

Pete: The point he is making, and I think maybe we’ve brought this home, is: manufacturing needs people. Without people, all of us, sharing a fair valuing of the worth of manufacturing, people won’t support it, people won’t find their way to it. From there, the loss of manufacturing will translate to a loss of the ability to innovate, and ultimately, we will cease to manufacture or to innovate, including in the very area of manufacturing technology itself.

So what do we do? Smith looks to academia, to engineering colleges, what they emphasize, and how they are even organized.

Scott Smith: There are people who don’t have any kind of a degree or only have a high school diploma. And they are, they can make good livings in manufacturing, but they have to, they have to be trained in how to use equipment and understand the equipment and be aware of what the equipment is doing and so on. That they have supervisory kind of roles for the equipment if we’re going to be productive. So that’s really important, but I mean, it’s a lot more than that. So we also lost the engineers who are going to design the machines and the software, who are going to lay out the plants, the facilities. Who is going to make the measurements of what the machines can do?

In many universities across the U.S. in the last few decades, they abandoned manufacturing as part of the curriculum. And it’s certainly easy to understand that, right? There’s risk involved. If there’s machines, somebody might get injured by a machine. The machines take up space. So they’re expensive. They’re expensive to buy generally, but they’re also expensive in terms of space. And then you have to hire people who know about them who can provide instruction. And, and so it’s costly to have manufacturing as part of the curriculum. And even the places where we have it. Manufacturing is treated like a sub-discipline. It’s like, it’s like, you know, thermodynamics is part of mechanical engineering, related to engine. But I think it’s the other way around. I think manufacturing is the superset that includes everything else. So it needs mechanical engineering, but it also needs electrical engineering, it needs industrial engineering, it needs chemical engineering, and all those things get combined in manufacturing sorts of activities. So I think abandoning manufacturing at university level was a was a big mistake.

Brent: But, coming back to an important point raised earlier, it’s certainly not just four-year colleges. It’s not just degreed engineers. Here is James Bessen, executive director of the Technology and Policy Research Initiative at Boston University School of Law, someone who has studied and written about the effect of public policy on manufacturing.

James Bessen: I feel very strongly about this. I think very much we’ve oversold, you know, there’s only one way to get educated… there’s only one way to get ahead in the world. And I think that’s been very detrimental. So we I think we need to have a better respect for vocational education, but we also think need to change what the nature of that is that, you know, again, vocational education isn’t going to be, you learn it for two years, and then you’re done for your entire career. It’s an ongoing process. And it’s also becoming closer to, you know, the curriculum of a of a pre-college program. You know, increasingly that the math skills that are needed in at least in some sectors of manufacturing are becoming more important. But I think more generally, we need to develop ways of nurturing mid-skilled jobs and channeling people into them, because that’s, you know, that’s what we did very well for a long period of time and manufacturing was a very large part of that. And it’s something that overall, we’re not doing very well at these days.

Brent: So how do we do better? How do we change what people think of when they think of manufacturing? Heidi Hostetter is taking steps in her area.

Heidi Hostetter: We take them on what we call institute tours. Like we take we talked to the major manufacturers out here and we we take them on tours. We take them on the tours of the otter boxes manufacturing site, Ball Aerospace, Lockheed Martin. We show them that other side of the business, the thousands of the world, we actually have set up through Noco, the sector partnership that you’ve heard me mention a couple times, and every state has one, by the way or multiple. We’ve decided to set up tours, so that the kids can go on those. We also have generated, like, what we call parents night out, where a couple times a year, the parents get to come into some of these facilities and really understands the nuances. Much better. You know, the goal is that they they leave knowing more than they came in and just putting manufacturers like myself out in front of the community, because you know, I’m not wearing a do rag and I don’t run around with grease on me and I have a pretty good life. Right.

Pete: No do-rag, she says. No Laverne & Shirley.

Brent: And no Lenny. And Squiggy.

So how should we think about careers in manufacturing? In a previous episode, we talked about the supply chain, a concept many of us discovered this year when it was severely disrupted for a brief period.

But through it all, through COVID, manufacturers found ways to continue producing, including making products that are important to us, and products that are vital to us.

Here is Randy Altschuler, CEO of Xometry, a digital marketplace for manufacturing sourcing. For Randy, the public view of manufacturing deserves a major correction:

Randy Altschuler: You know, I think it’s very interesting. and rightfully so, we applaud first responders in the United States. So if your child, you need to be concerned about their safety, but if they became a police person or a firefighter or a doctor or nurse, you know, we recognize the social good that they’re doing there. And that they’re that they’re ready to go into, you know, teachers who are helping all of us, maybe not for the highest income, but for a noble cause. I don’t think you have that respect for manufacturers. And I think the more we can trumpet that fact… and again, this is a tough time for this to do this. You hate to say it, but if people aren’t making things the rest of us can’t survive. Somebody has to make the trucks that are carrying that food that’s going to the supermarkets while we all stay, you know, a lot of people stay from home. Somebody has to pay for the infrastructure, all these different things that require actual fabrication of parts.

And again, our national security is often on the line for this. I think we need to trumpet it. And they get a heroic profession where we recognize that it’s super important. And you just don’t have that recognition or admiration. And we need to we need to give that, we need to excite our, you know, girls and boys to grow up and to being manufacturers. And I think one of the things that even for the technology people that we recruited is Xometry because we have a lot of software developers, one of the things that gets them going is the fact that we make real stuff. And I think there just needs to be more of that. That is something that we want our kids to do to produce — a tangible good with their hands, even the machines doing, they’re pressing the buttons, something tangible gets done. That’s freakin’ awesome.

Brent: I’ll just finish with this: when it comes to post-secondary education, four-year institutions versus trade schools and technical colleges, it’s really a both/and situation, I would argue.

I worked in higher ed for years. And I will defend the importance of a degree in the humanities to the bitter end.

But there’s also this whole other option that is just as important, and — if we are talking about actual, real life, right-now needs in our country — probably more important. There are pathways to very lucrative careers in manufacturing that require far less formal education than a Bachelor’s degree. I literally just interviewed a guy in his mid-30s who went straight from high school into work at a machine shop, where he learned CNC programming and machining, became proficient with CAD modeling software, and is now super successful running his own business.

His path to success might look very different than a quote unquote “traditional path.” And the problem with that falls squarely on how we define a successful career path.

Pete: So actually, I think this is a tide that is turning. We’re in Generation X, you and I. And I think we got the worst of it. For our parents and for baby boomers, manufacturing jobs, jobs at the plant, were often Plan B, what you did if other options didn’t pan out, our parents didn’t want that for us didn’t want us to have to settle for the fallback. The idea was work with your head, not your hands. That was the distinction. And also back then, when Generation X was going through its teens, the 1980s that’s when it seemed there were all these plant closings, layoffs everywhere. As we’ve documented, the bigger employment declines in manufacturing, we’re still to come. But it was starting then.

And really visible then, in the 1980s, Billy Joel sang Allentown, and that song will always be with me, because those lyrics were all about that all about manufacturing transition. It’s like that song and the news of the world was punctuating what our parents wanted to say about manufacturing. But now, now we have to unwind out of every one of those assumptions. What used to be in those big plants is now in many cases, dispersed across a chain or a network of various smaller, specialized, more technological, different kinds of facilities. The future for manufacturing is bright, because as we’ve been describing, we made some wrong turns in the past, we’re going to set right, the pressure is now on manufacturing to grow in the U.S. It needs people, it needs talent, and then that idea: work with your head, not your hands. Boy, we have to rethink that one. We have to shift our assumptions because the work of skilled manufacturing is mental, intellectual labor more than it ever has been. Its programming planning, interpreting measurements, working with technology, between the person working in manufacturing and the person working in the service sector say, is it really clear which of those is working with their hands more than the other. The last piece that really has to give is the expectation of four-year college. This is a hard one because no parent wants to see their child make a choice that might limit their future to less than it might be. And two years versus four years feels like doing less. But there are technical professions where direct engagement with the technology is the path rather than theory or book learning, valuable work that needs to be done, where the education looks that way, and we can serve people well by guiding more of them into that path and better honoring that path.

Brent: Made in the USA is a production of Modern Machine Shop and published by Gardner Business Media. This episode was written and produced by Peter Zelinski and by me. I also edit the show. The series sponsor is… Hardinge.

Made in the USA was recorded at the historic Herzog Studio, home of the non-profit Cincinnati USA Music Heritage Foundation. Our outro theme song is “Back Home” by The Hiders.

If you are enjoying this series, would you please leave a nice review? If you’re using Apple Podcasts it’s super easy, you just tap the fifth star on the main page of the show… I can even wait… I’ll just wait… Ok cool, it you did that, thank you.

If you have comments or questions, email us at madeintheusa@gardnerweb.com. Or check us out at mmsonline.com/madeintheusapodcast.

The above is a complete transcript for Episode 4 of the “Made in the USA” podcast. In addition to the hosts, the commentary in this episode is provided by:

- Randy Altschuler, CEO, Xometry

- James Bessen, Professor, Boston University School of Law

- Mike DiMarino, President, Linda Tool

- Heidi Hostetter, Vice President, Fauston Tool & CEO/Founder, H2 Manufacturing Solutions

- Rob Ireton, Former Plant Manager, Plethora

- Scott Smith, Group Leader, Intelligent Machine Tools, Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- Doug Woods, President, The Association for Manufacturing Technology (AMT)